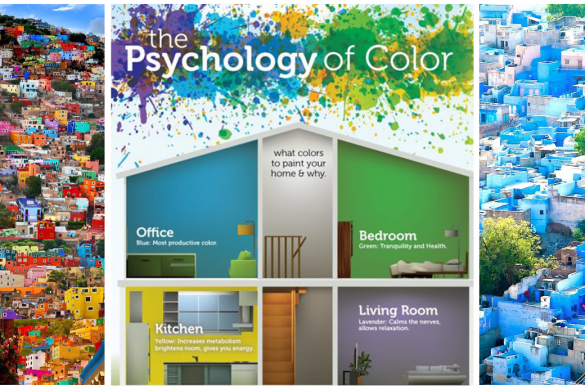

We’ve seen and read and heard about the meaning of colours—across cultures, across time, across topics, and even across people with different visual abilities (i.e. blind, colour-blind, etc.).

At the most simplistic levels, we know red stands for danger, stop; green is for all-clear, go; yellow is for caution, slow; pink went from being manly to effeminate, and so on.

It’s clear that colours are imbued with meaning, based on context, culture and time.

But I want to pause for a minute and ask the reverse question: is it colours that have meaning, or is it meaning that we ascribe colour to? Why, and how?

Take the cacophony surrounding intolerance in the country right now. How do some people ascribe saffron to right wing intolerance? And how do some others imbue extremism with the colour green?

For centuries the colour of royal blood has been termed to be blue. In one fell swoop, an athletic brand turned this ancient order on its head when it asked a billion Indian citizens to bleed blue over a cricket trophy.

How did we take positivity as a point-of-view about the world and decide it was rose-tinted?

Communists are red. They were also pinkies.

Fresh, inexperienced people are green.

Evil is black.

Pure is white.

Depression is blue.

Cowardice is yellow.

Seduction is scarlet.

So, why and how do we ascribe colour to meaning?

The why is fathomable. We’re wired to deal with complexity by finding and creating shortcuts that make it easier for us to recognize things, put some method to madness, and to expend less brain in dealing with things that we encounter time and again, or in multiple places. And colours, in some sense, are labels we give to stereotypes and archetypes, to phenomena we believe we, and others, will encounter more than once. They are an easy descriptor for complex metaphors and analogies.

What’s fascinating is the how of it. How, for example, did we decide cowardice is yellow? A quick trawl through the internet doesn’t deliver any convincing answers. The explanations range from jaundice (itself derived from jaune, the French word for yellow) weakening a person and making him or her too feeble to display any strength / courage, to the peculiar yellow belly skin of the 18th century inhabitants of the Lincolnshire Fens in the U.K., to yellow bile being one of the four humors (fluids) of the human body. Why, when yellow otherwise is the colour of sunshine and all things cheerful, the meaning of cowardice was imbued with the colour yellow, is a little mystifying.

Purity’s association with white, meanwhile, seems to have arisen not because of white’s spotlessness so much as the ability of even a smidgeon of dirt to destroy the colour. Pure, by association, was that which could be destroyed by even a smidgeon of doubt.

A range of passions—from love and seduction to anger, courage, health and vigour — are associated with one colour, red. This seems to have mainly physiological origins, in that the suffusion of blood, itself red in colour, to the face is plainly visible in the arousal of any of the passions.

Evil’s association with black comes from darkness — the period where our main sense of perceiving things, our eyes, becomes useless. Darkness is the phenomenon that renders things mysterious and beyond our perception. With our inherent desire to believe in goodness and the forces of good — seemingly within our comprehension — evil goes beyond our ken. We are unable to fathom why people would be driven to evil acts, and hence, by association with other things beyond our comprehension — like the darkness, we term them black acts.

As the modern-day example of the athletic brand and the blue-bleeding billion indicates, though, it is possible for culture and context to bend even the most established associations between meaning and colour. To what end is an altogether different question though.

Image Courtesy: Google Free Images

1 comment

Like brand names, colours can be imbued with meaning.

The ‘leftist’ association with the colour red was because the communists appropriated the colour. And being a pinko was a useful way for Americans to describe those who were sympathetic to communism.

I believe cultures attribute meaning to colour with the meaning they attach to those colours through repeated use in that cultures rituals.

Thought provoking post, Anisha.